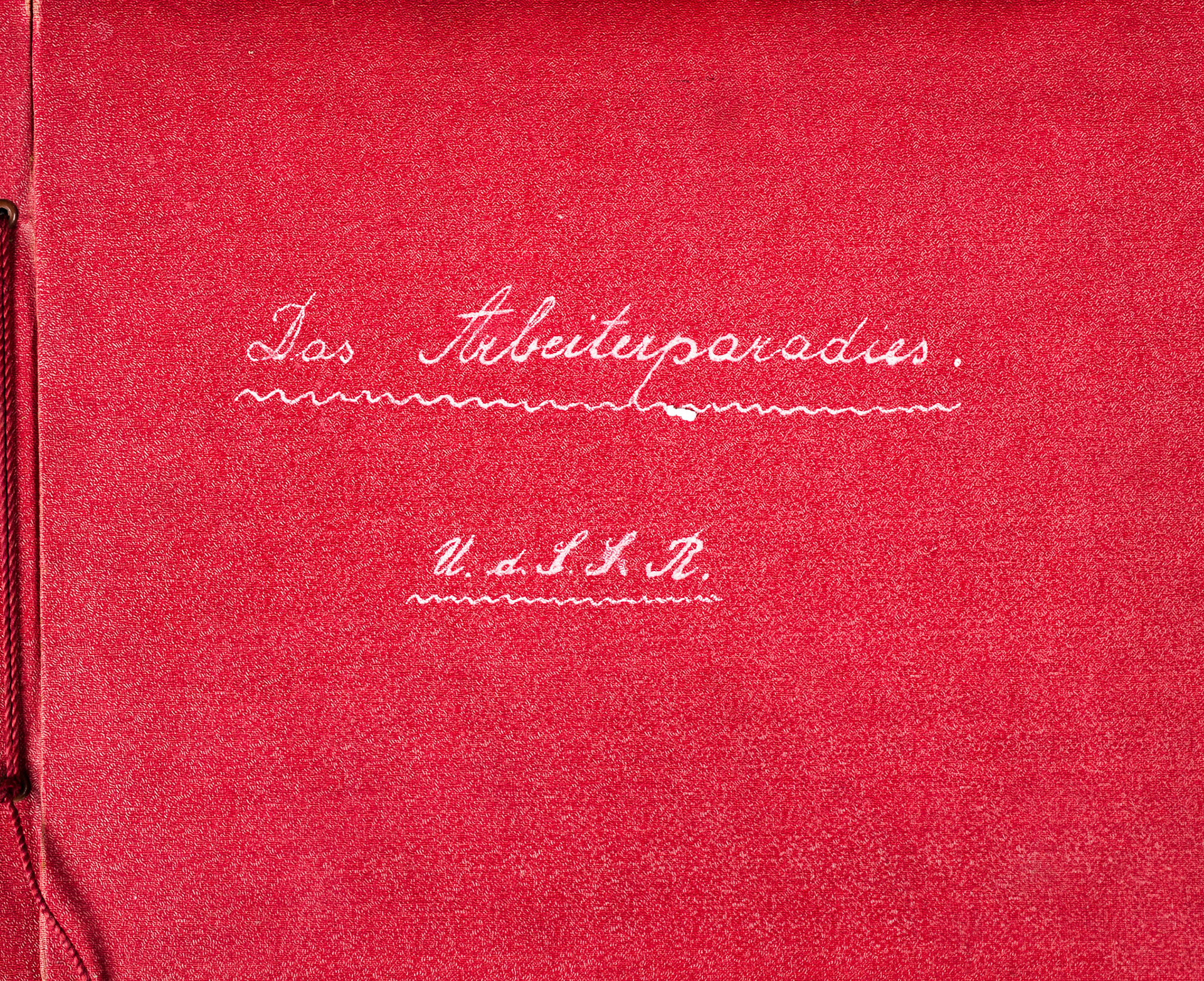

Nina’s Memories of the Holodomor

My dad refused to join the collective farm. He decided not to give up and instead of joining the collective farm; he got hired as a railway worker. He was working as a cargo examiner. We were Polish nationality.

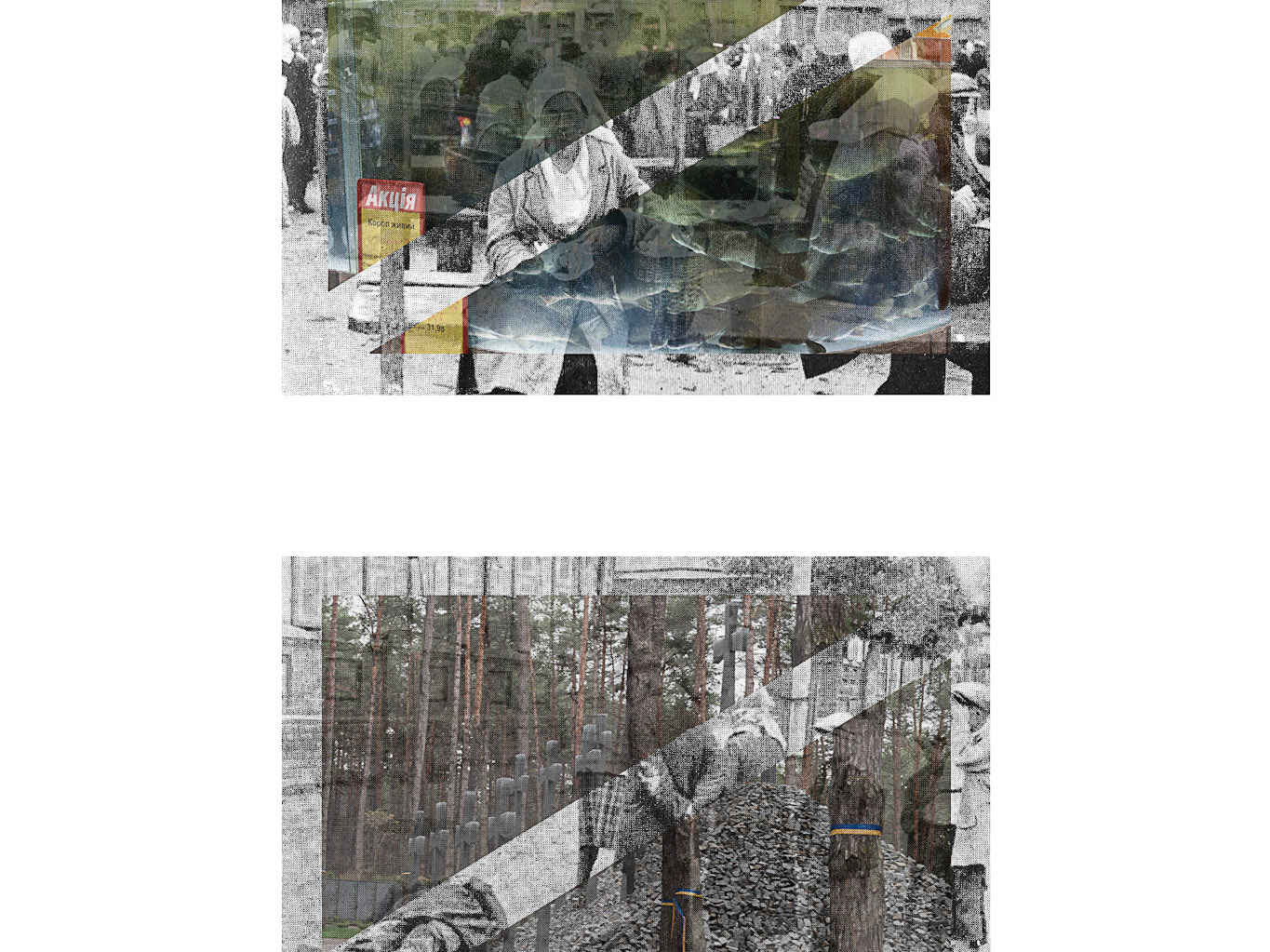

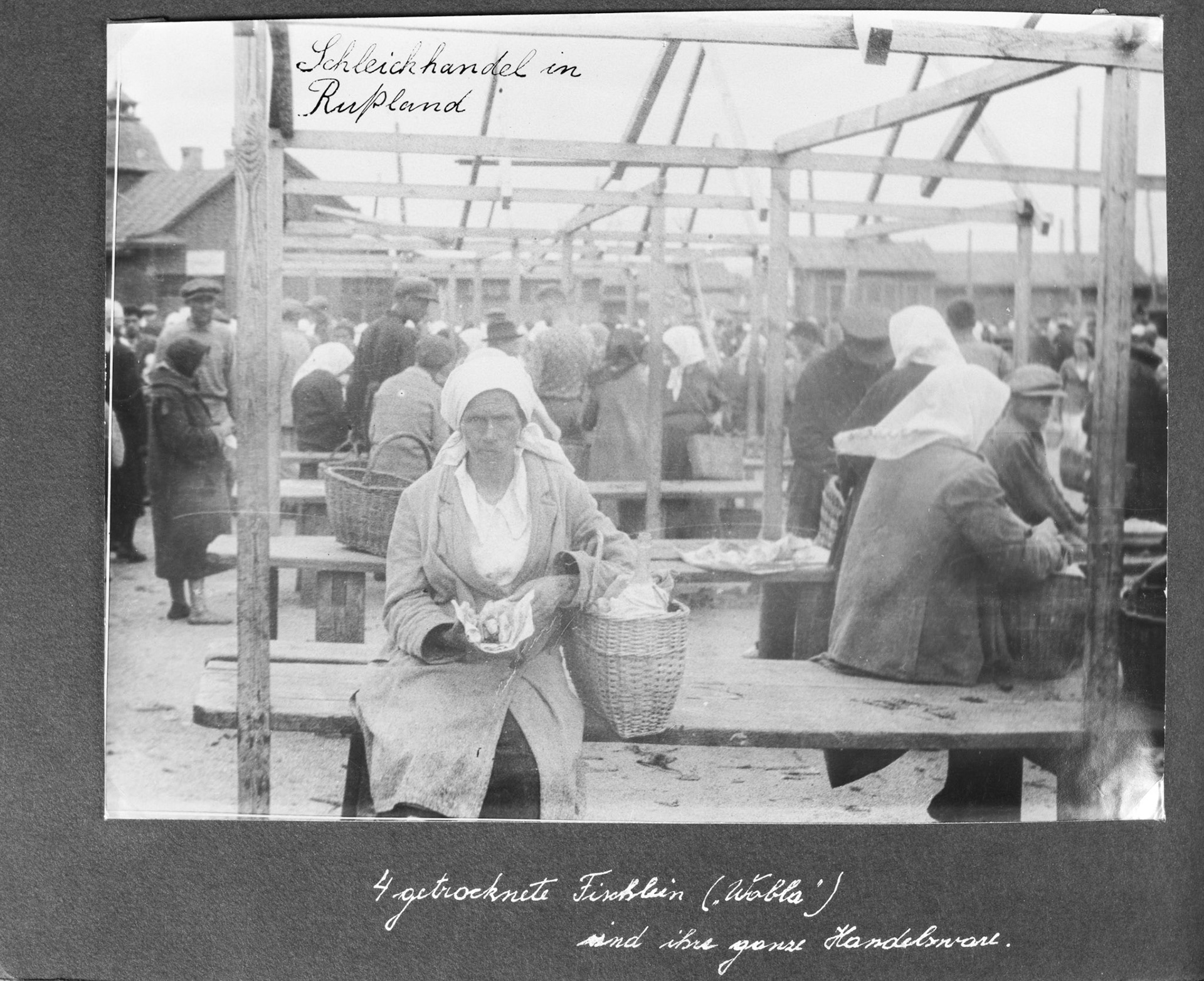

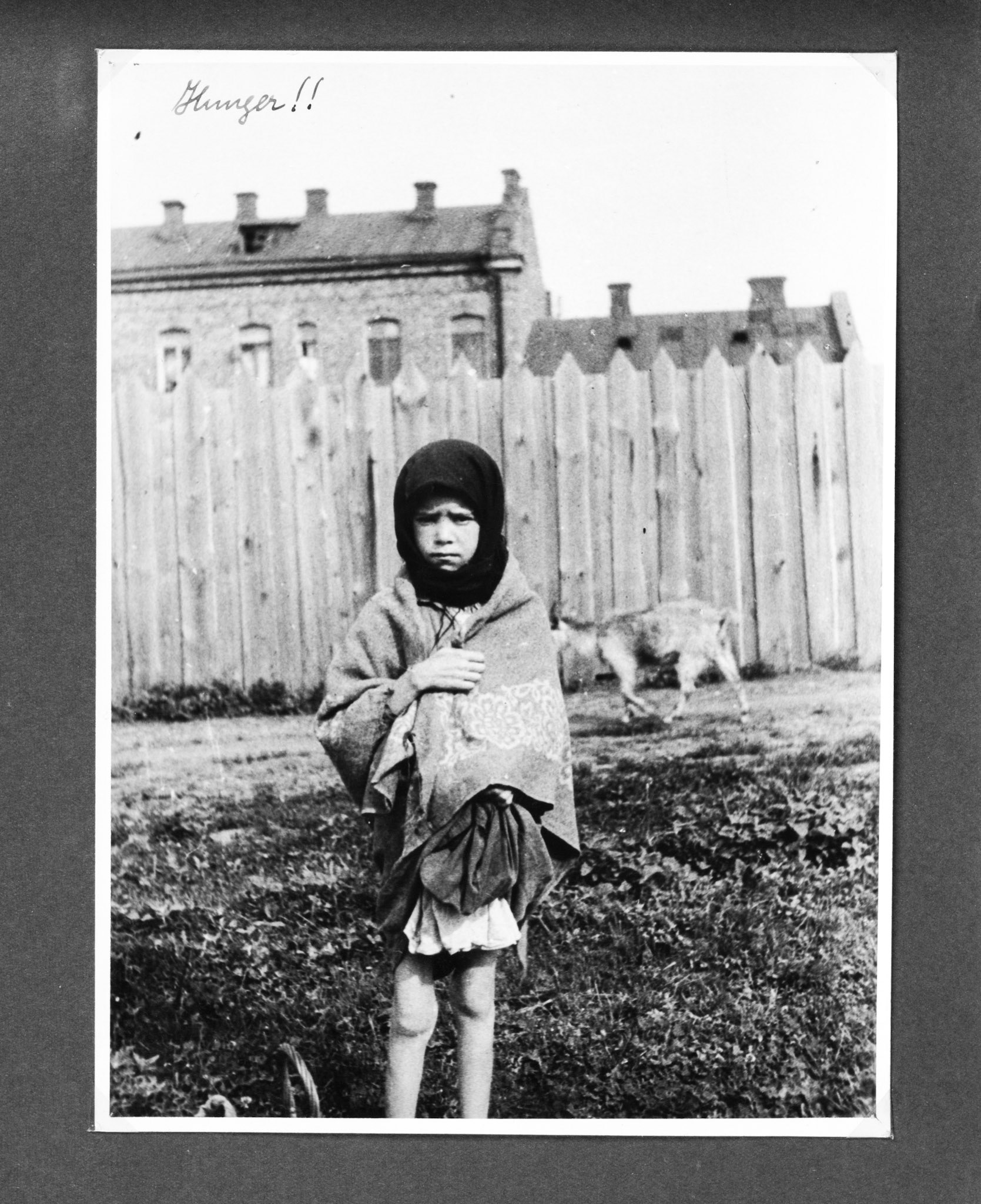

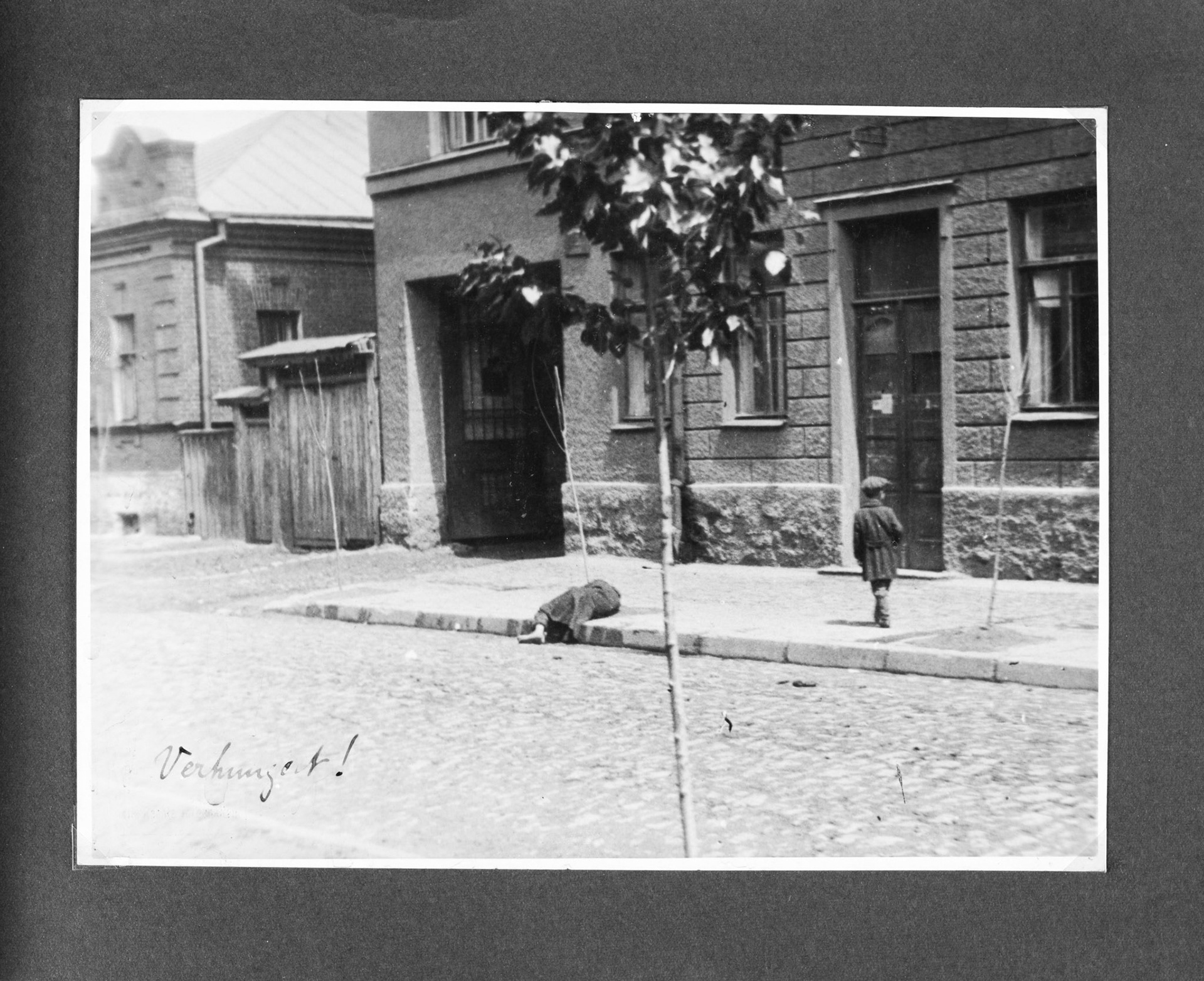

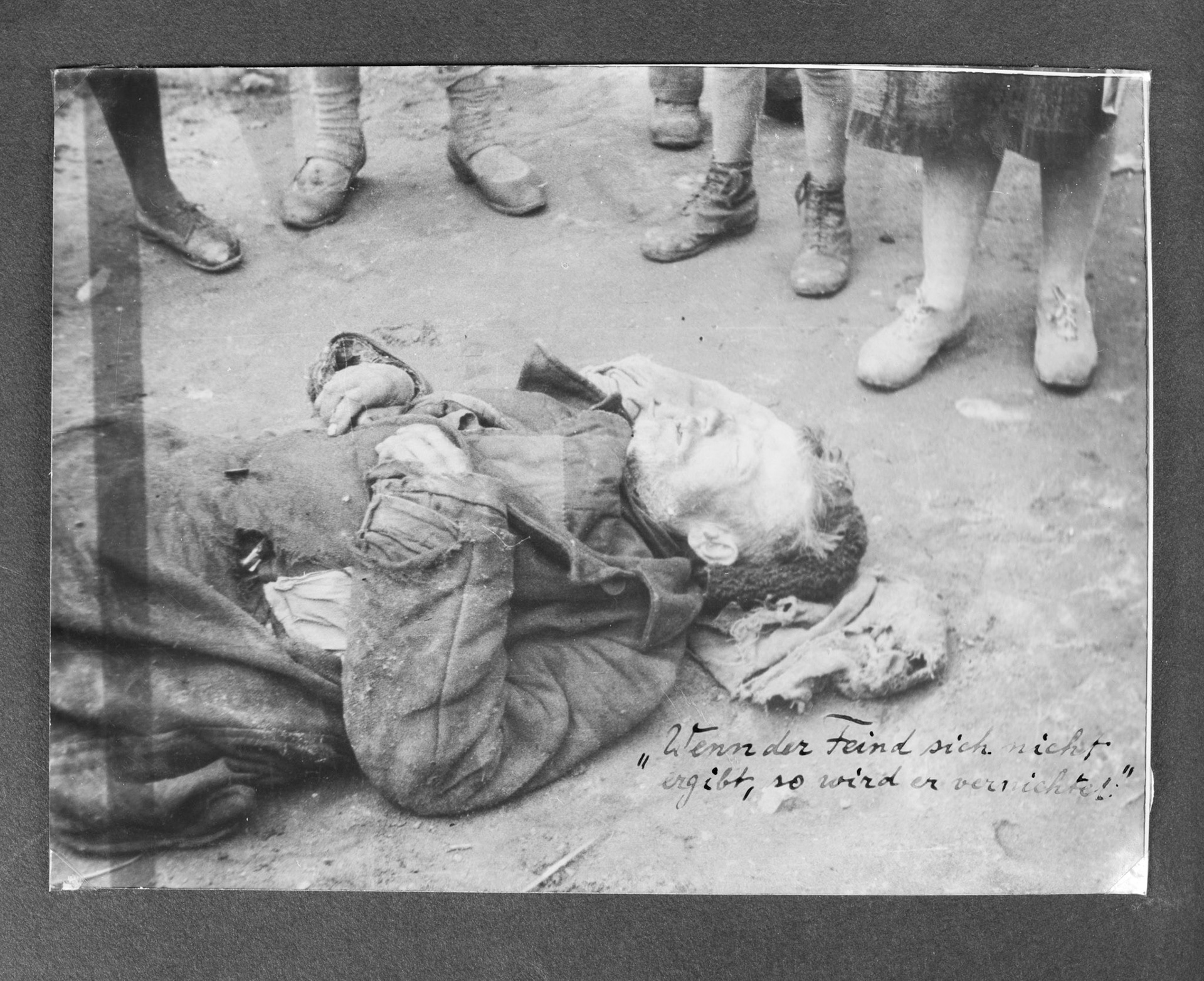

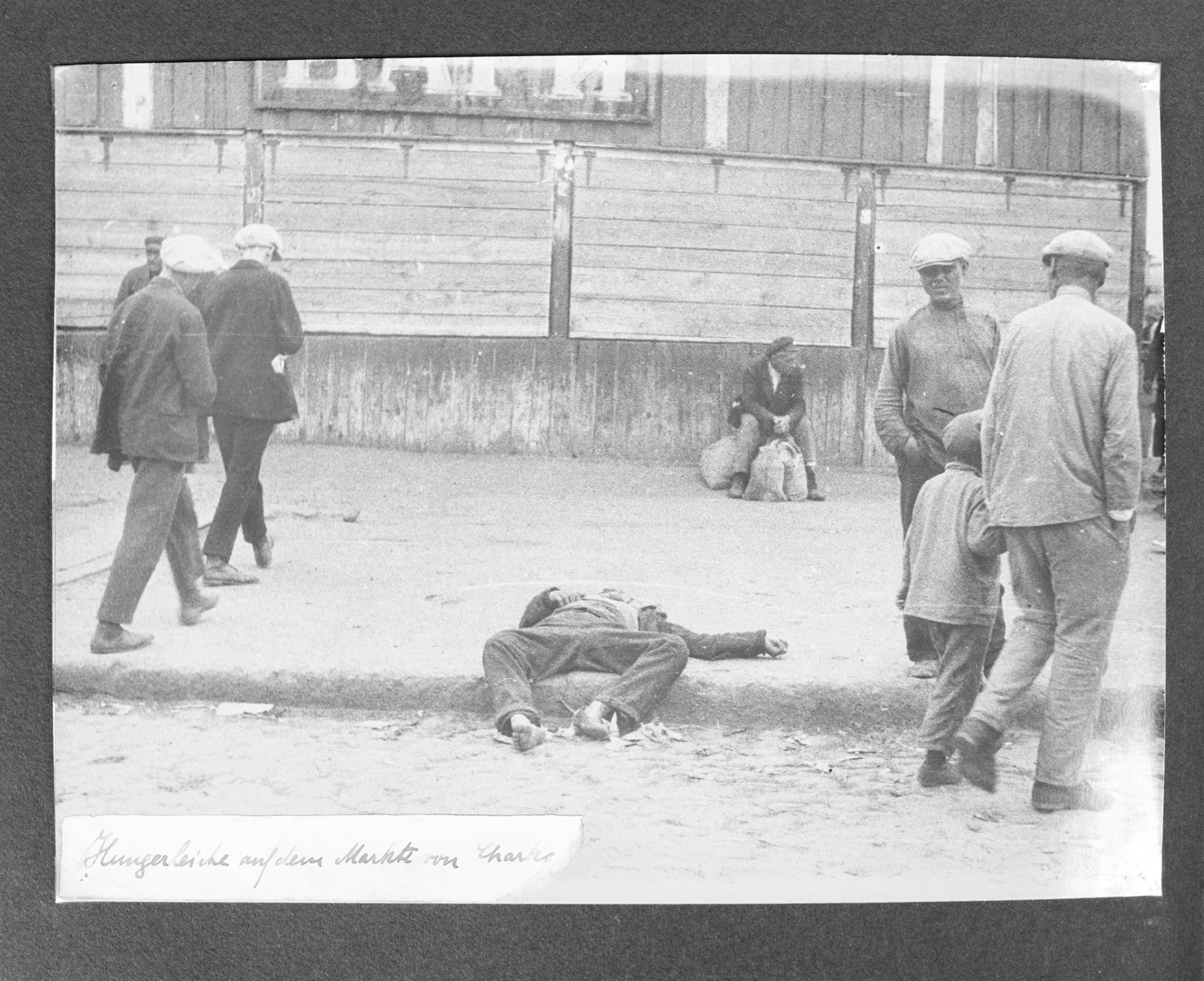

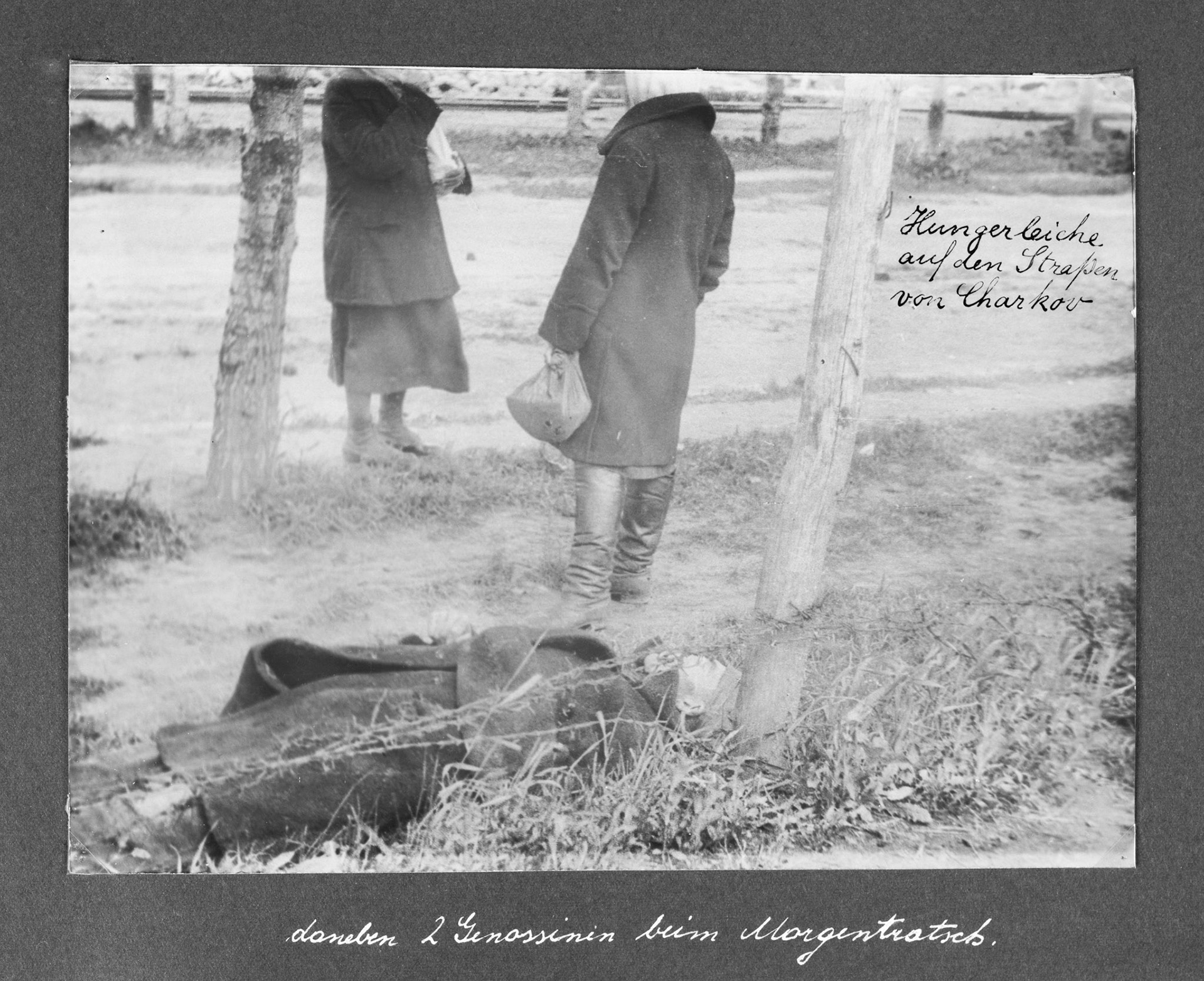

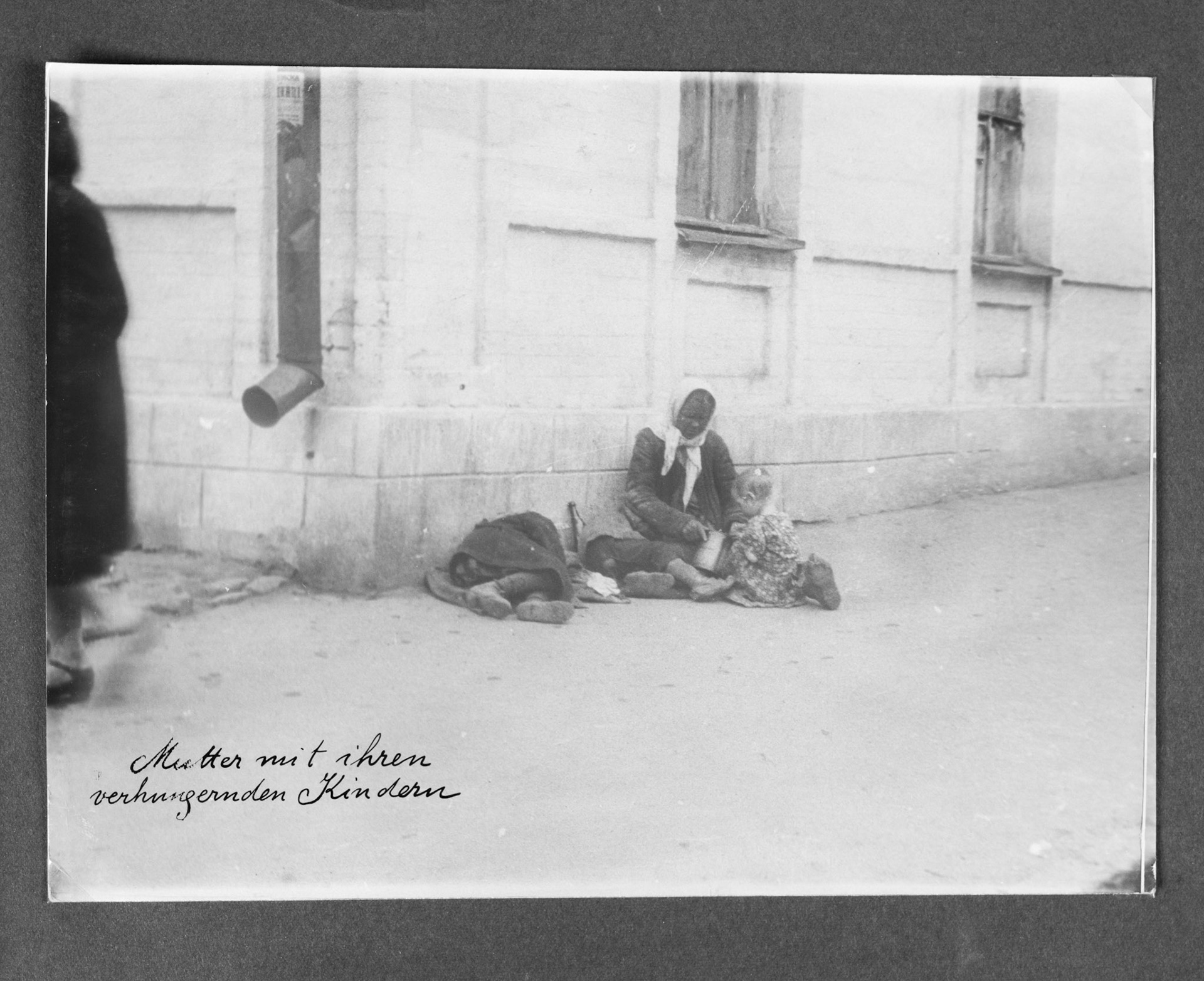

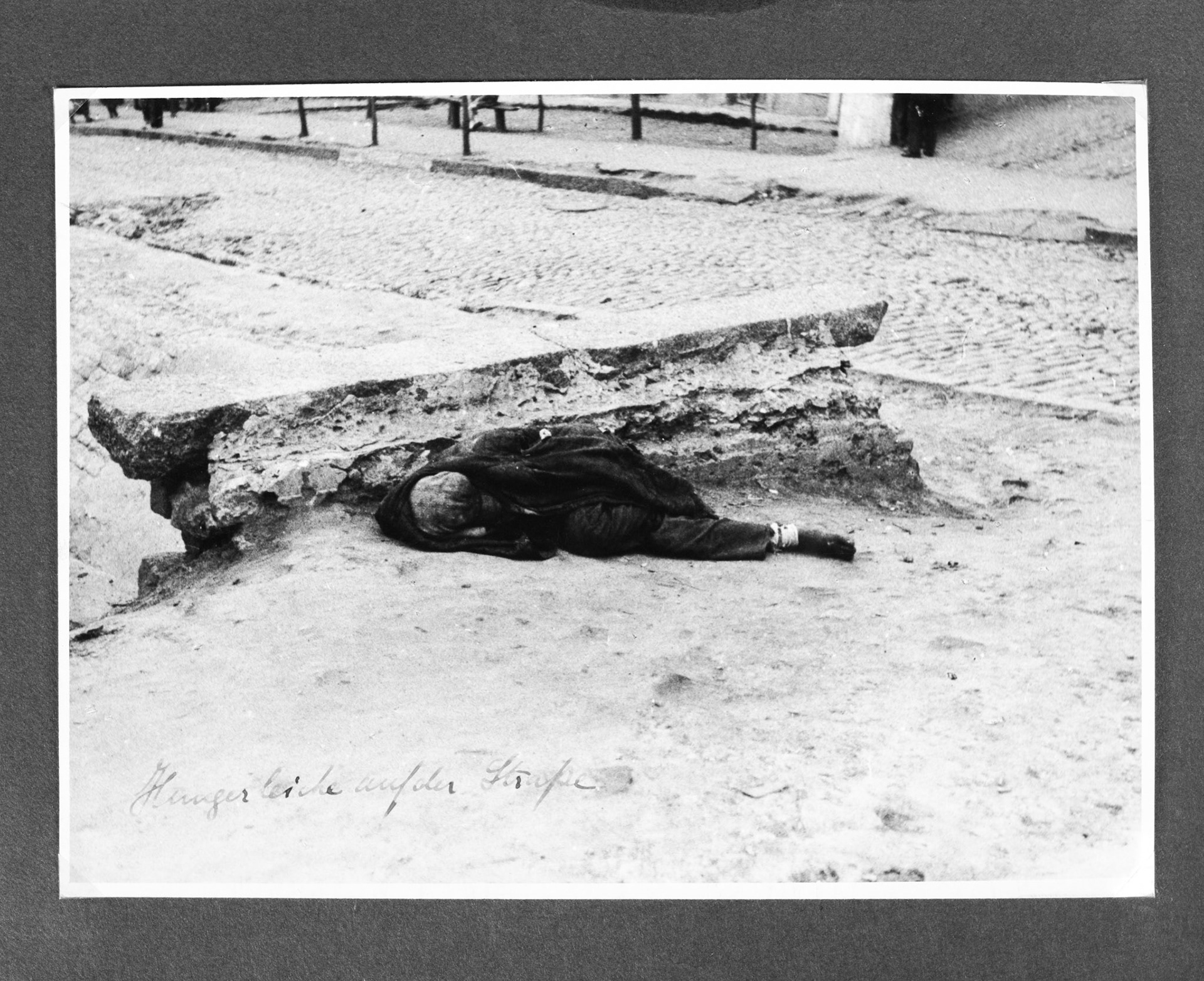

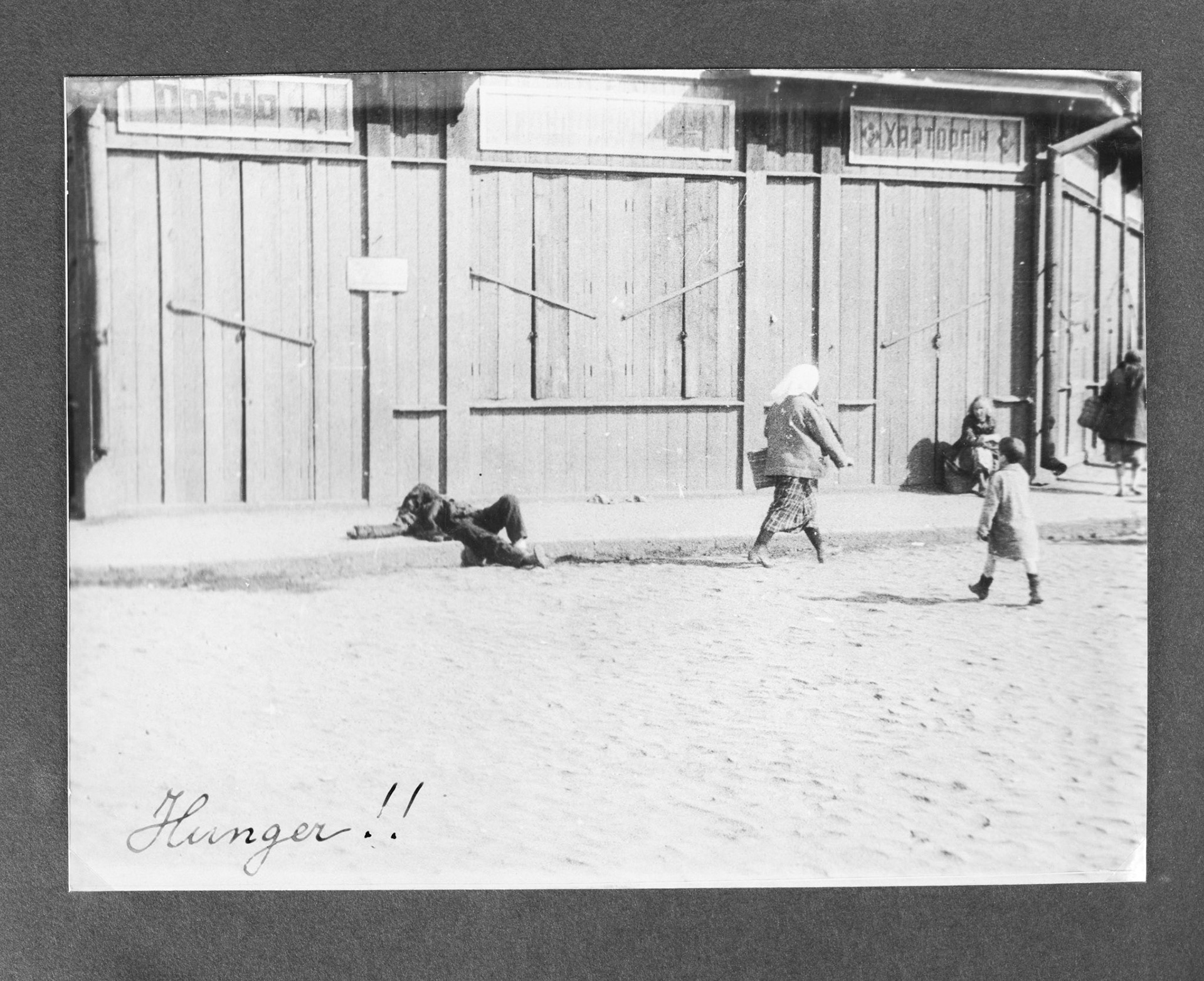

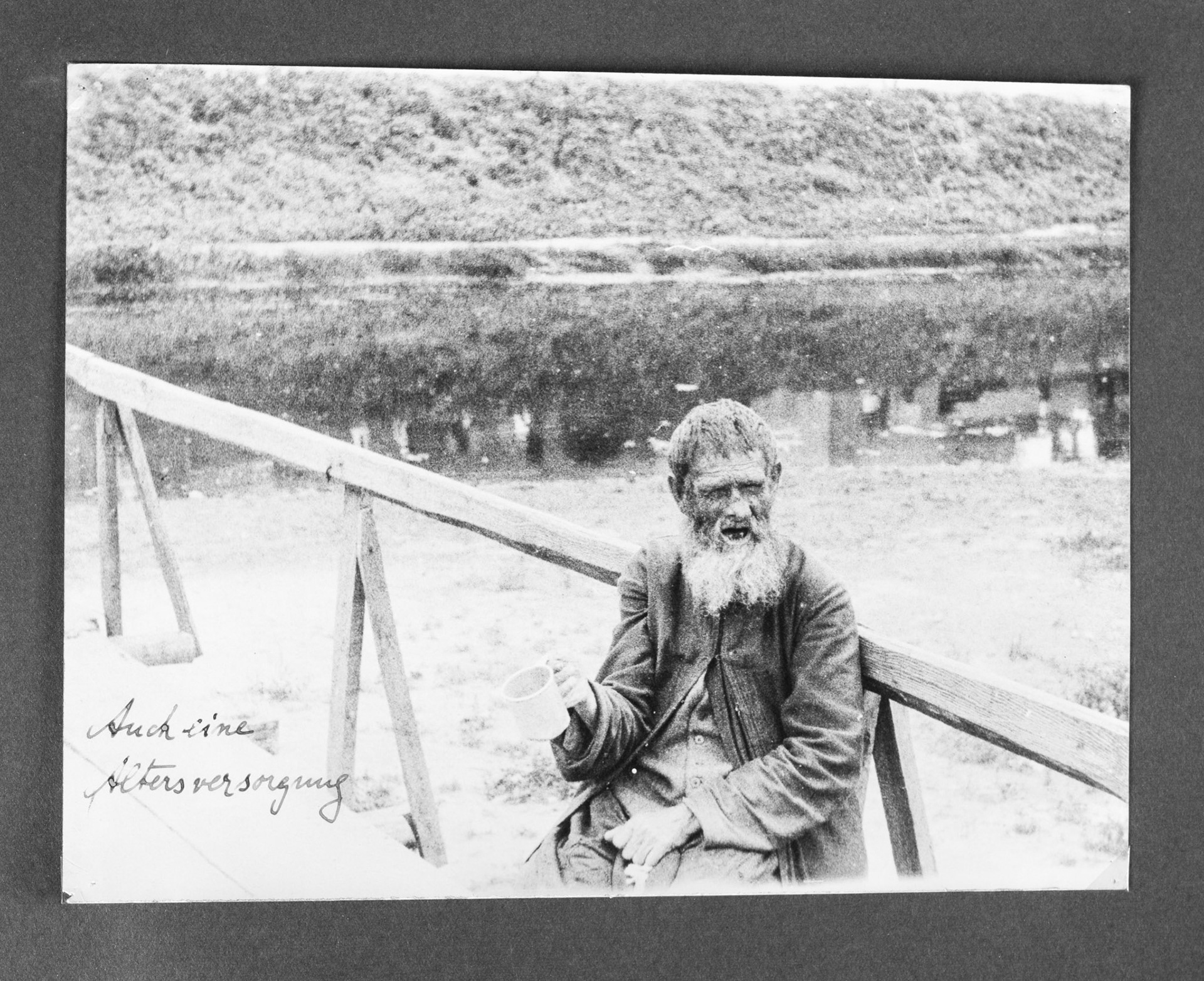

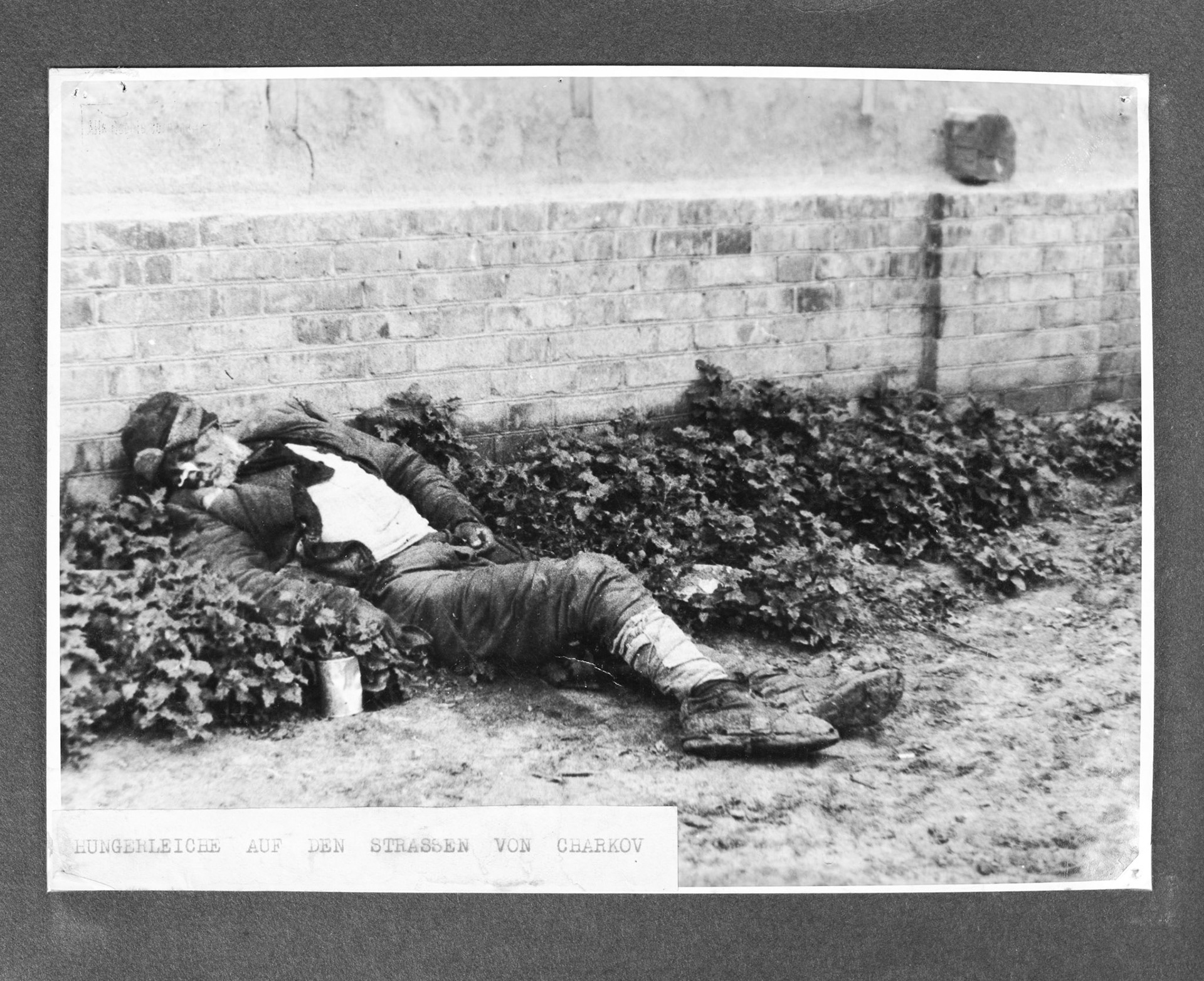

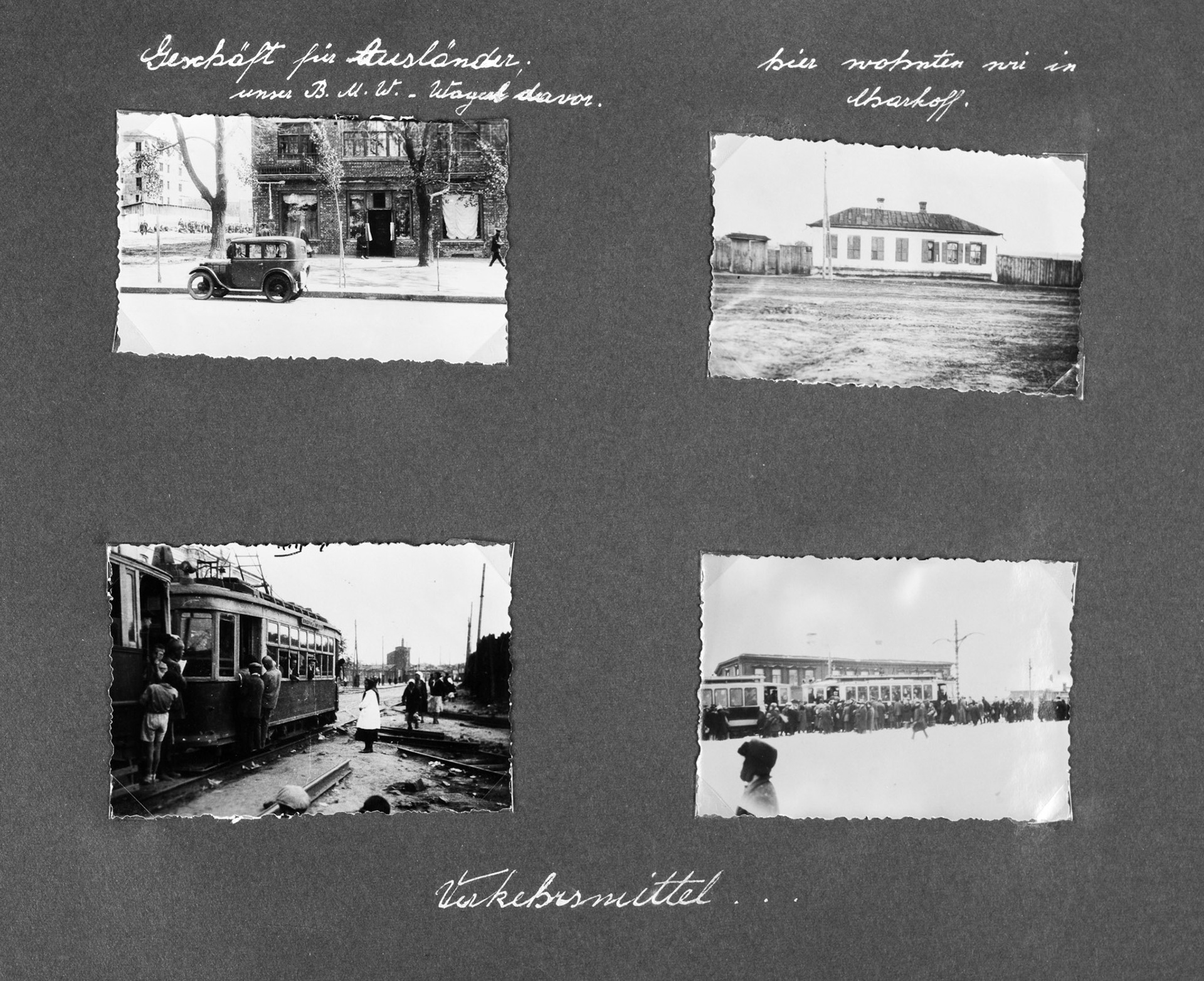

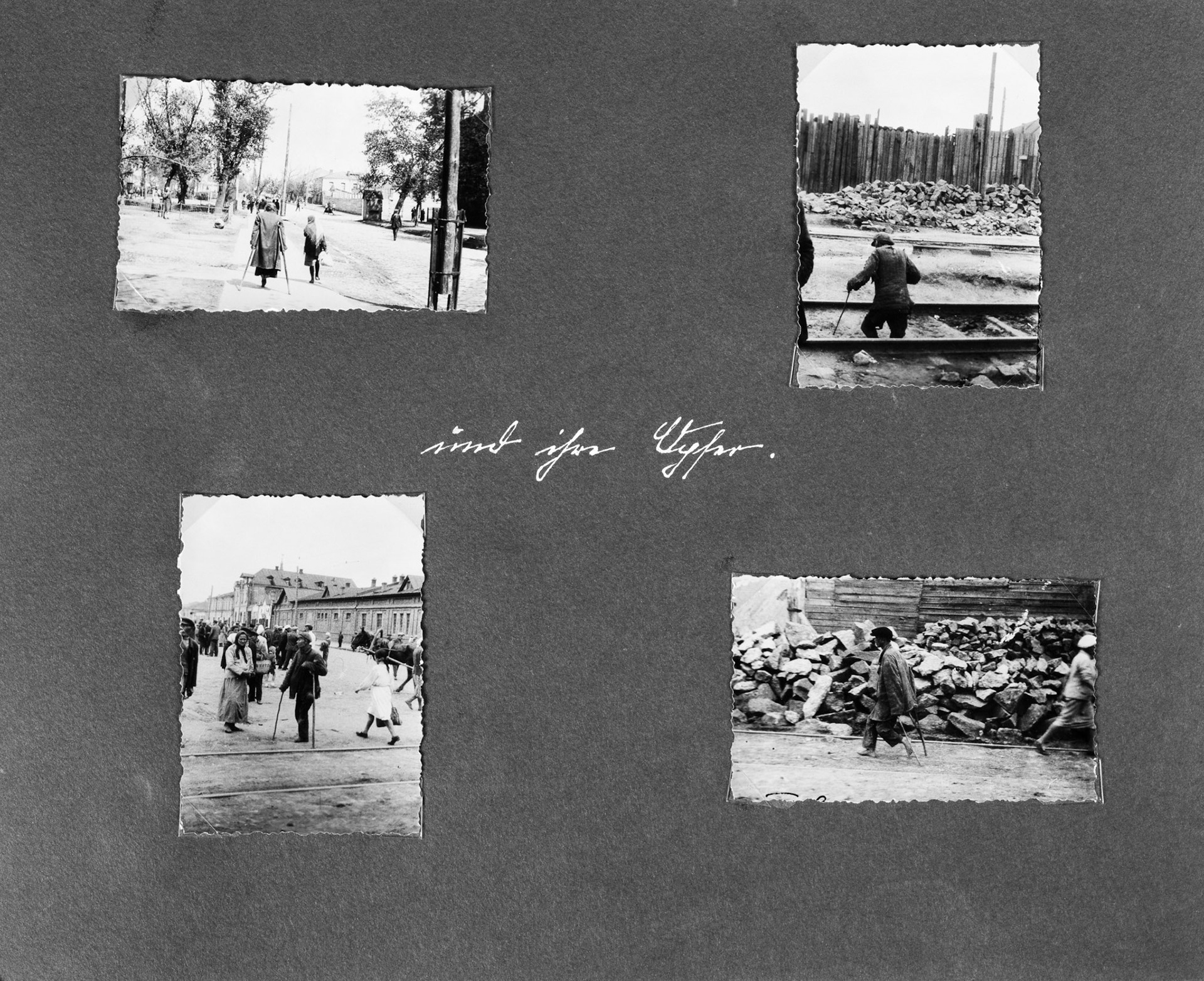

My father was a worker, he was entitled to food, each worker had a small cart and they were allowed to get one loaf of bread. He was allowed this because he worked but people around, like farmers working at collective farms, didn’t get any food at all. Corpses were just lying around on the ground; it was a very severe time. My father was working in shifts, night shifts and day shifts. When he was at work he was able to get that loaf of bread and bring it home and when he was off work, I had to walk 5-8 km to stand in a big line to get a very small loaf of bread.

It did not matter how many people you had in the house because the one working person is entitled to just one loaf. We were lucky, there was only three in my family and when my dad was off, I would run back and forth to get this bread. Sometimes it would take up most of my day to get bread.

All strong males were striving to get ahead [of the bread line] and I was a very small girl. The man in charge would say ‘No, no, no. That small girl should be first.’ And he tried to pamper me and give me some of his bread. And in 1937, December 24th it was Polish Christmas and that night the KGB came into our house, took my father and his brother. My father had six brothers.

My father was accused of supporting Poland because he stored a lot of saint icons at home, so he was taken by the secret service, at night. He was kept in a prison 40 km from here. Those who wished not to admit to their guilt were beaten, sometimes to death. My father said, those who did not agree to the accusations were taken for an investigation and after the investigation they were not allowed to come back [to the prison] on their own. They were brought back, covered in blood, sometimes unconscious. My father saw this and thought there was no way he could escape, ‘they will beat what they want out of me.’ So, he signed all accusations.

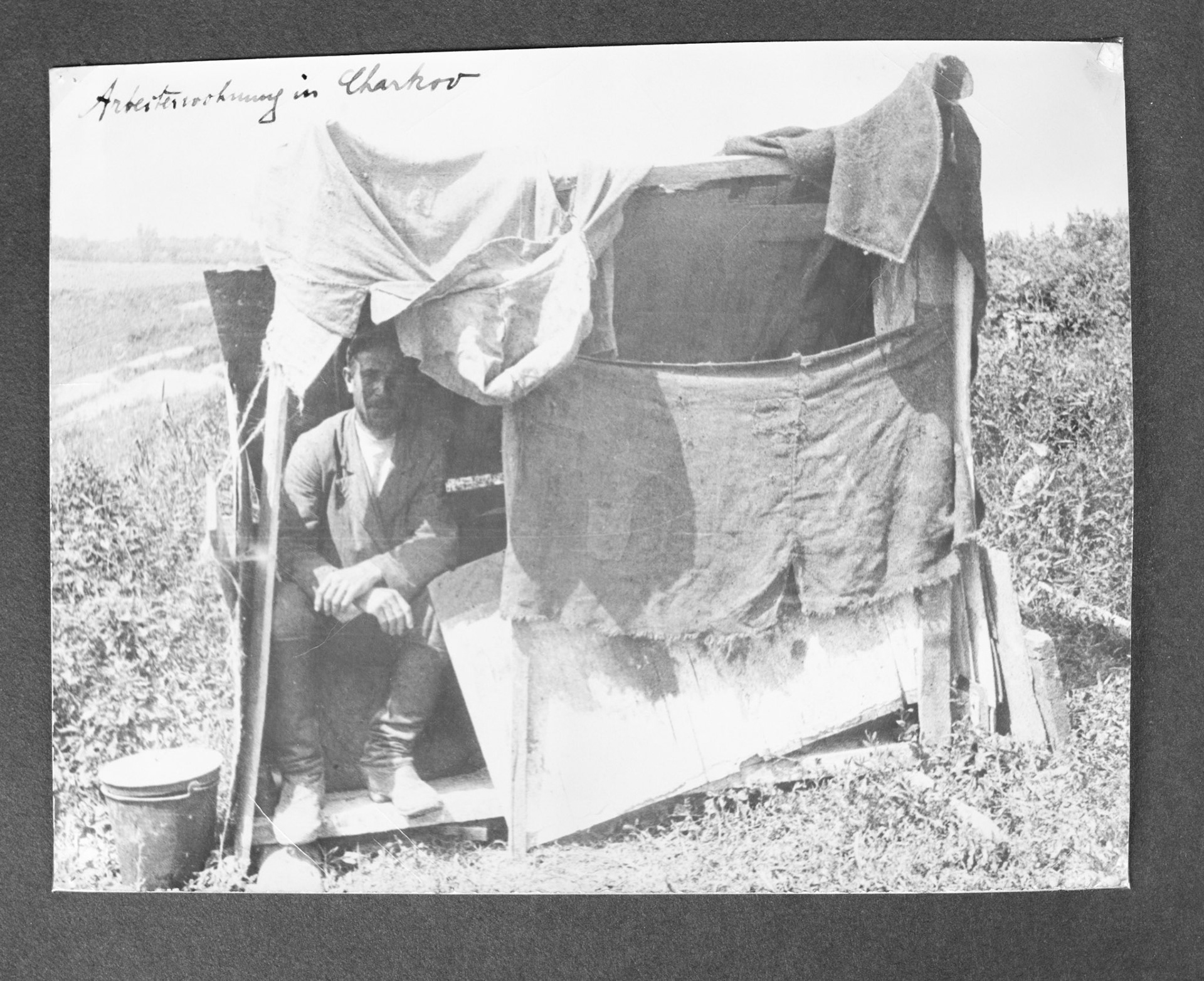

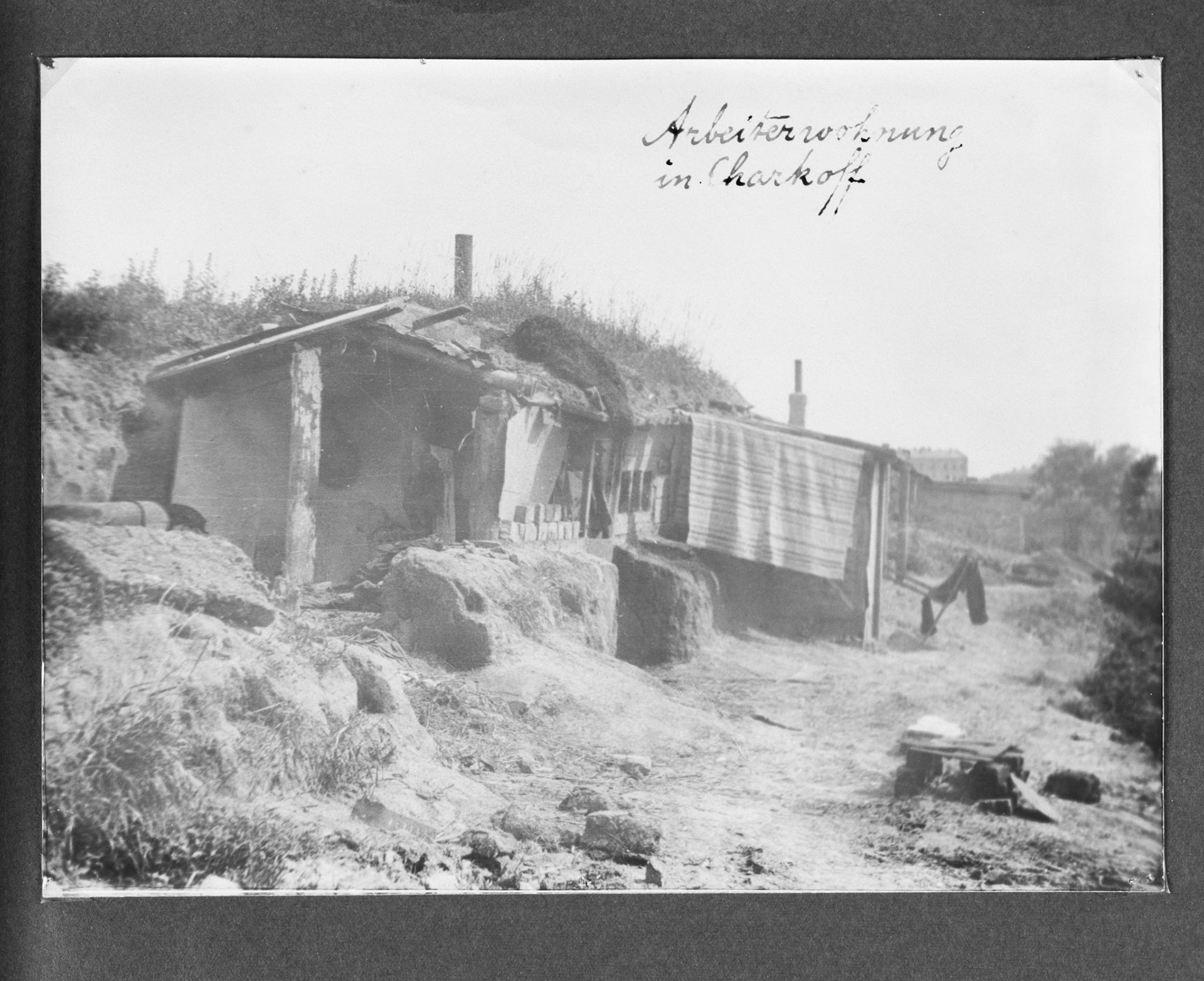

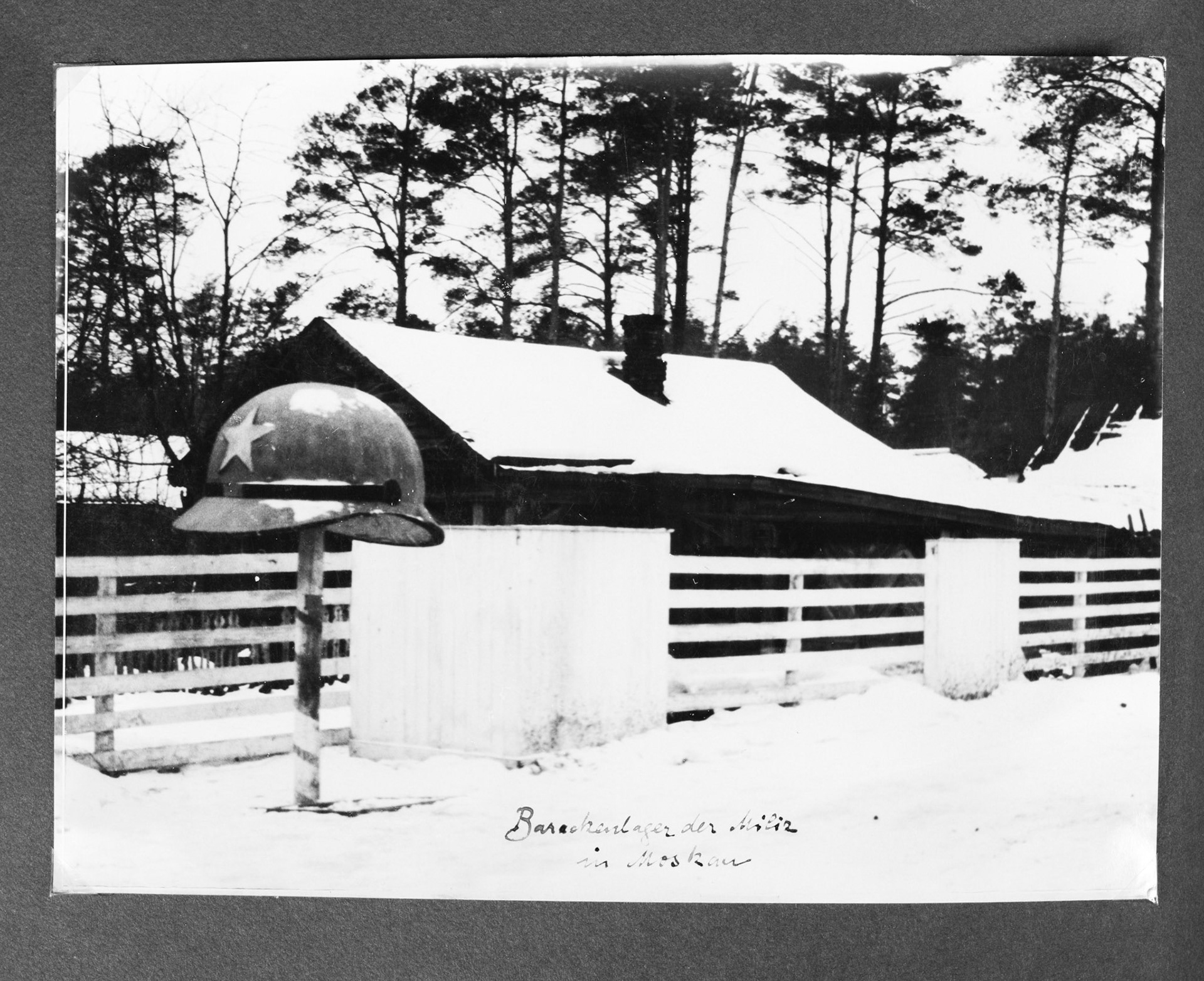

At first my father spent a little time in Moscow, then he was sent to another prison further north and at the time this place was nothing but forest. Too many prisoners were kept there, like doctors, directors, stock managers, politicians, it was a mix of people. The first two months he was closely supervised in custody and monitored by the prison warden.

When he was allowed to host visitors at the far north gulag camp, I took a train and went to see him. I was allowed to see him for five days, it took me one week to travel one way, and so I only travelled there twice. When I got there I had blisters because it was a lot of travelling, I applied for medical care and a very pretty woman offered to help dressed like a doctor. I asked her what she was doing in this godforsaken place, ‘you are pretty, and you are smart.’

And she said she was the same as my father, incarcerated and suppressed in the gulag camp. As well as my dad there were other men who were kept there and no-body came back. When the war broke out in 1941, they just disappeared.

I will try to go back a little to Holodomor. People were looted, everything was taken away from them and they were forced to join collective farms. My parents had two hectares of land; they kept some calves, chickens and two horses. They worked very hard to survive and my dad didn’t want to join the collective farm and every thing was taken from us.

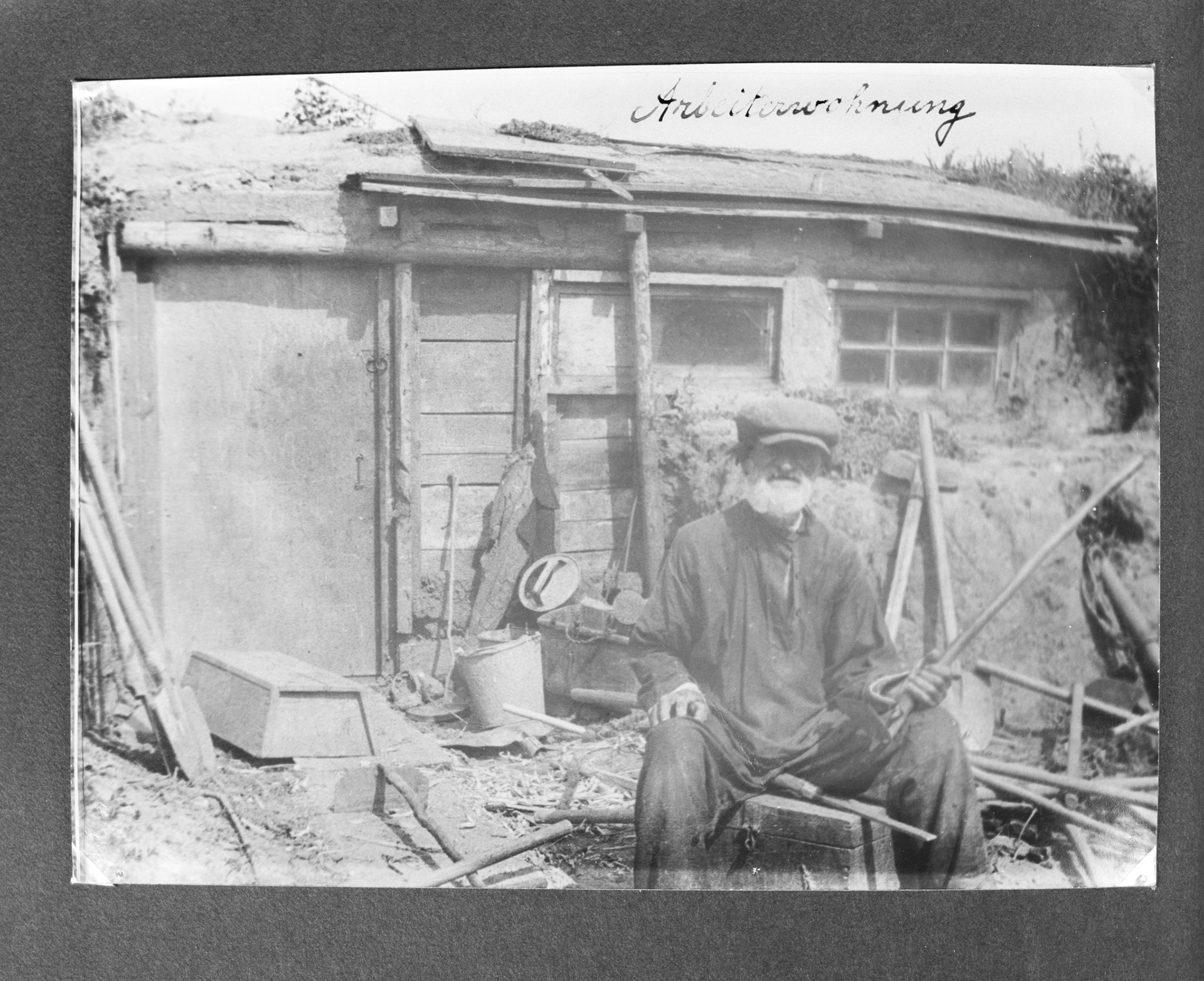

My dad was named a so-called kulak and they evicted us out of our house, we left with nothing. It was November/December in the early 1930’s, at the beginning of collectivisation and we were kept in a barn and our house was put up for auction. We managed to buy our own house back but after my dad was taken we were classed as an enemy of the state, we were marked as enemy of the people.

I was attending school, but there was no school in the village, I had to travel everyday when it was good conditions. There was a school in the village but it only went up to grade seven and I was in the eighth grade, so I was meant to attend the school in the town. My uncle used to live in the town and when it was very cold my mother kindly requested that I would stay with him. To get from school to home I would have to get a regional train that was used to transporting workers and I was expected to sit and wait till very late at the railway terminal.

Even after the war we were considered enemy of the state, only after Stalin’s death and Nikita Khrushchev came to power were we no longer marked. After Stalin’s death we were allowed to live an ordinary life, we were don’t deprived of things. To be honest I cannot tell you [if I was treated differently because of my background.]

I was attending a local catholic church but I could not tell you if I was treated different because of my Polish background, it was a very difficult time. I am about to turn eighty-eight and I still remember these things.

Of course my childhood was spoilt, I did not get any privileges. If you compare it with other Ukrainian kids who were not marked as an enemy of the state, they had some kind of privileges. Since my childhood years I was deprived of any proper treatment, after the war I had two kids and I could not take them to kindergarten. They did not get proper treatment because I was an enemy of the state and I had to baby-sit them, so I could not work on the collective farm.

I was taken to court and sentenced to six months compulsory work because I was not able to join the collective farm. In 1949, I was sentenced and when I had completed the compulsory work, my husband thought it would be better to get out of our village, to get out of any collective farms and take a piece of land here, where I live today and build a house. We did not have any relations with collective farms. One of my daughters graduated from the university and my other daughter [Oleksandr’s mother] graduated from medical school.

Nina Dudnik; Interviewed by Samara Pearce

10th November 2012